This is a controversial blog. It may cause current leaders to feel uncomfortable, and I’m sorry for that as many are fantastic. Believe it or not, this is not about the quality of any leader, it is instead about the environment in which they function. I’m going to try and stay light on the theory, and instead paint a readable picture that may illustrate some of the problems I have seen and experienced. I’m hoping that sharing them shines a light on some of the issues with change in policing.

There are a couple of things we need to understand about the particular structural make-up of the cops before we go any further. To all intents and purposes, the police is still a job for life. Once you are in, the regulations that govern us as servants of the crown are robust. It isn’t rare to see people begin talking about how much service they have left within their probation (the first two years) – it’s a discussion that runs through the fabric of the job. Many discuss their plans for retirement and plan their mortgages and debt around the commutation. There are many cops that discuss, ‘seeing their time out,’ and ‘making the finishing line,’ and these time based conversations happen everyday around you. Of course, they don’t by proxy mean that people’s enthusiasm begins to wane in their twilight years in the job, and there some fantastic cops in their final years of service. But, make no mistake, the length of service is a BIG thing. People will introduce themselves, and in the same breath tell you how long they have in the job. Experience over time isn’t just important, it is the way that people judge your level of knowledge. If you have many years in, the assumption is that you are ‘good’ cop, able to operate within the system and navigate from A to B competently.

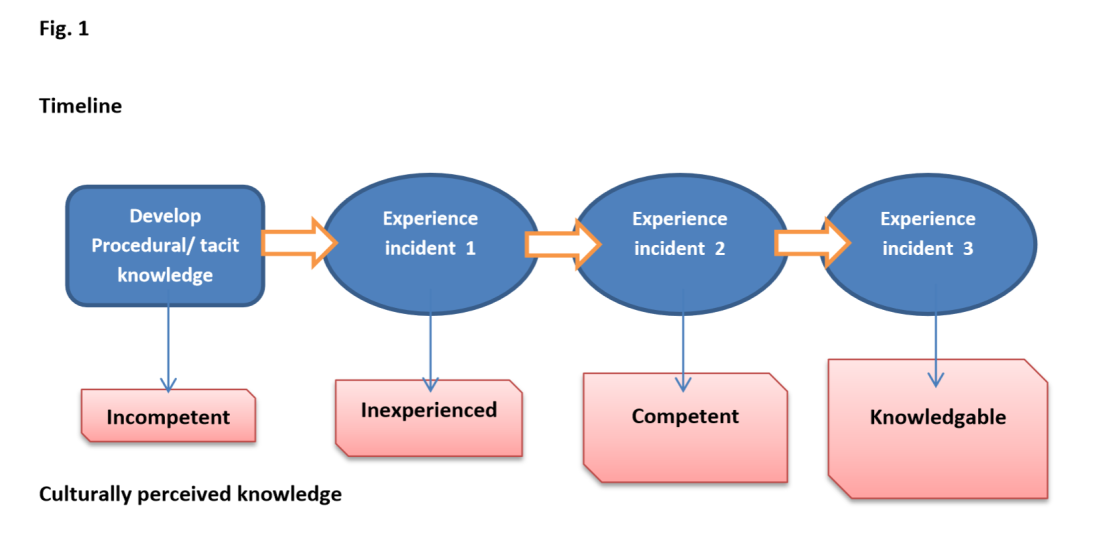

A simple model of this would look like:

This connection of ‘time served’ to competence isn’t just a cop thing, but the 30-39 year tenure frames a particular discussion within the police that simply doesn’t take place elsewhere. On twitter and in service, I’ve been asked, ‘Oh yeah, and how long have you got in?” Let’s translate this: “If you have not X years of service, I’m afraid I won’t even listen to you.” How does this manifest itself physically?

- Probationers have to make the brews.

- Probationers get the worst jobs, repeatedly.

- Probationers are often asked to stay quiet or ignored by some until they become regulars.

- Probationers often are last in the leave rota.

- Probationers get the worst vehicles.

- Probationers are last out of the carrier.

- Probationers are called ‘probey,’ or something similar, until they have the service in to be called by their first name.

This list isn’t exhaustive, but I’ve seen this still happening within the last few years. If you were coming into the profession, and this was ‘the way we do things around here,’ what would you think? You would immediately have to accept the fact that ‘time-served’ was really important, and you would also have to accept that your opportunity to learn would be really limited by the work you were ‘allowed’ to do. A quick example – if as the shift probationer you get every bed-watch, or every constant supervision, the chances are you will learn at a VERY slow rate. Most of your time will be spent on your own, watching people sleep, or talking with prisoners. Some hate this with a passion, but no one will challenge it, and it still remains the norm in many places now.

Taken to its extreme, this can be seen as individual bullying, but I don’t subscribe to that, it’s just culture doing culture’s thing. It’s not a productive thing – it can feel deeply hostile – and in fact it actively works against probationers taking any responsibility, or doing any deep learning at difficult jobs. Of course, inevitably as probationers pass their probation, some haven’t actually dealt with anything ‘hooky’, so we actually can’t judge how they will survive as a regular officer.

Let’s look at the fallacy of time-served = competence

Probationers can just be bloody amazing. As a supervisor I’ve worked with a few that put those with far longer service to shame. In fact, there’s one probationer I can remember, who was one of the best cops I’ve ever worked with within 18 months of joining. To put him on a bed watch was a total waste of talent – for both the service and the public. At the same time, on the same shift, there was a cop with over 15 years’ service who really struggled dealing with anything much more complicated than a shoplifter and was persistently lazy. Funnily enough, he talked about length of service a lot. Time-served just didn’t equal competence then, and it doesn’t now. As a supervisor, I looked after that probationer, and although he took his fair share of bed-watches, I would have much rather have had him out and dealing with the public.

This primacy of experience manifests itself in other ways too. Those older in service won’t listen to the ‘whipper-snappers’, and ‘experience teaches best’ is mantra for the collection of work-based knowledge. We even discuss ‘time-served’ in promotion, so you may have been given the advice:

- I’m sorry, don’t go for your next promotion, you haven’t got enough time in rank yet.

- Don’t even apply, you need to have worked in neighbourhood policing.

- I’m sorry, you haven’t worked in a strategic/operations position yet.

- Come back next time, it’s not your turn.

- There are others ahead of you (this isn’t a competence thing, it’s a ‘They were here before you,’ thing).

All of the above comments are pretty much about length of service. You can colour them up, but they essentially mean, ‘Go and collect a few more years.’ Importantly, they don’t ask valid questions like:

- Is this the best person to go into neighbourhood policing?

- Is this person with less service of a higher competence than the person with longer service?

- Should this be about whose turn it is, or who would provide the best service for the public?

- Would putting this person into an Ops based role displace someone of greater skill in that role already?

- Is this person’s talents aligned with their position in the job – because that is where they will give the best service and enjoy the job most.

To give you an idea of how the above examples can be totally dysfunctional:

Person A is great at their job and a natural leader whose staff show them a lot of respect. They ask their line supervisor for a shot at promotion, and they are promptly told that they need some neighbourhood experience before they apply. They don’t really like neighbourhood policing, and prefer the fast paced action of response policing and crisis management. The management want them as a supervisor though, so a move is engineered and Person A does a job-swap with Person B. Person B has been a Neighbourhood supervisor for many years, prefers long term problem solving and has firm established partnerships with many people in the community who feel that they are indispensable. They don’t get time for a job handover.

Person A is well out of their comfort zone. Over time they manage a few community relationships, and find remote supervision of the team difficult. They dislike the community meetings and want to solve problems quickly and decisively. This doesn’t fit with the ward area and they are soon receiving complaints from residents. Their wellbeing suffers, but they soldier on, knowing they have been asked to do at least 18 months.

Person B is also well out of their comfort zone. They need re-skilling and disappear to do several courses, whilst resourcing organises cover – leaving another team short. Fast paced decision making isn’t their thing and the team find them frustrating as they second guess themselves. A few practical mistakes and they are under investigation for their competence and on an action plan. This results in time off sick and a need for cover for them. This means a once stable team with a well liked supervisor receives inconsistent supervision and persistent staff shortages. Their wellbeing begins to suffer too.

All of the above happens, because the force wants their supervision to have spent time in neighbourhood policing… They want ‘time-served’ in a particular role, despite the fact that the candidate – in both cases – is unsuitable. And the really sticky bit, is that neighbourhood policing isn’t – in any way – a pre-requisite for good leadership. Good leadership is just good leadership, and it matters not how much service you have or where you have served it.

And the weird thing is, that the level of competence isn’t discussed either? At promo time: “I see you’ve done your time on Neighbourhoods. You’re eligible now.” – No mention of the fact that they really struggled there, or that the move cause organisational problems across two departments… Box ticked, applicant clearly a far better leader now…

This kind of example becomes even more problematic when you look at other industry. You would never hear of an accountant who couldn’t get promoted because they haven’t done a stint in HR, and if there ever were any swaps between those two functions, the staff member would have to fully re-train. Can you imagine someone working in construction being told that they can’t go into management until they’ve spent time as an electrician? What would they say? ‘I don’t need to be an electrician, there’s plenty of electricians who do that.’ It’s just weird that the cops do it, and the main argument that is used doesn’t ring true either:

‘You need omni-competence to be a good leader.‘

What is omni-competence? It’s competence around a wide group of specialisms, so as a leader, you need operational, strategic, and investigative experience, because experiencing all these things makes you a better leader.

Does it?? Says who? I know great investigative leaders who’ve been in investigation all their career. I know great operational leaders who have spent all their career in ops. Moving either of those people out of those spheres would be a travesty, because they are truly awesome in their respective fields, yet it happened. It stands to reason that the service levels would then drop, as others with far less experience take over, so that they can move into an area where their knowledge is of little use? I bet using the ‘5 whys’ (when you ask ‘why’ 5 times to see if you get a meaningful answer) this would falter at stage 2 or 3. There’s no evidence behind it.

Why does this happen? I guess there’s a presumption that we get good leaders if we bounce them around the organisation? It’s like an organisational habit. We’re addicted to it. The result is an inconsistency of leadership, many, many courses (and therefore expense) as people constantly collect competencies (that they use for a very short amount of time), and a discernible lack of strategy across the organisation. How do you execute a five year or ten year strategy when you change leaders every 12-18 months? It would be incredibly difficult. The end result is plethora of short term changes, and a lack of any long term vision. This is why cops on the deck feel the brunt of initiative after initiative from new leaders trying to make their mark, before their stint ends or they get switched elsewhere.

If you have spent 20+ years doing this, it’s the path that you have taken, and you place value in it. At the bottom of the organisation you accept that this is the way it works, and you play the game and do the time. In turn, you value the time spent on other things, because there is no way that people don’t learn when they change departments. The learning curve is steep, and you have to learn fast to fit in and keep the wheels turning. This personal learning is great for that individual, but for the service, and for the public, I’m not sure it’s great at all. In fact, one could even say that people are paddling so fast under the surface as the run the ‘job-switch’ gauntlet, that changing the way things are done – and I mean properly changing them, not tinkering and doing little initiatives – becomes an impossibility.

At the level of middle managers, when you have the greatest opportunity to make a tangible difference, you are on the ‘job-switch’ gauntlet. You navigate hoop after hoop, because those ahead of you choose if you progress, and those under you don’t seem to factor in whether you get promoted or not. You need to fit in and deliver for the gatekeepers, not those that sit outside the keep. Ambition keeps you on the ‘job-switch’ gauntlet, and the culture becomes self-sustaining. At the promotion boards, there are lots of discussions of what you have done, where you have done it, and what ‘competencies you have fulfilled’ (think experience as knowledge as I discussed above). This is embedded in the National Police Promotion Framework, which measures your answers on the ability to relay previous experiences. Prospective leaders must be collectors of experience and tellers of stories.

They often don’t have to prove any external learning, they often don’t discuss how they would change the future, they often don’t discuss their knowledge of culture, they often don’t discuss their self-awareness or self-reflection, there is little exploration of emotional intelligence or resilience, and they rarely – if ever – evidence their personal knowledge of how others view them. God forbid them discussing mistakes… (the greatest source of learning).

A changing of the guard?

The name of this blog was chosen not because the guard is changing, but to discuss how a ‘change’ is incredibly difficult. Whilst experience and time-served is valued over the things in the above paragraph, how can we ever do a meaningful job of developing them? If, for your next promotion you have to do Neighbourhood Policing, because that’s what the boss said, or that’s what the boss did, why would you invest in Continuing Professional Development? If you are asked to hoop jump and run initiatives, why would you delve into self-awareness and self-reflection? If it’s ‘your turn next,’ why would you look to changing the future landscape?

And herein lies the major problem. Whilst the gatekeepers hold the keys to the gate, why would they change the gate?

If our current leaders had to do ABC, they will place value in ABC. Why would a current leader suddenly start asking for DEF? It would be like them admitting that their leadership development had been poor and that experience in department X was only a small part of being a leader – when that experience had gotten them to where they are today. And if ABC got them up there, the surely it will be OK in the future? Let’s throw some hypotheticals up around this:

“Don’t believe all this guff about self-awareness and emotional intelligence, it’s this year’s garlic bread. Just go onto department X and deliver for me.”

“Don’t worry about all this academic learning. I didn’t do it. It’s experience that matters and years on the streets.”

“There’s nothing wrong with our culture. Don’t listen to all the naysayers, the service is in fine shape. It’s your turn in the next board, just keep your head down.”

I’ve heard/seen some of these things first hand. It’s the gatekeepers putting trust in their gate. They guard the paths to progress in the job, and in doing so they hold the key to real culture change. Where does it begin? When the Sgt signs off a PC’s performance development review with ‘suitable for promotion,’ all the way up to NPCC. When the gathering of ‘experience’ is the ‘way things get done round here,’ it will continue to be closely guarded by the key holders, who saw success off the gathering of experience.

So, if you want change in a culture like this, how do you go about it?

You have to have a serious think about the structure of that gate, and who holds the responsibility of looking after the keys. In a job where there is a long tenure by default, those keys are closely guarded and surrounded by a network of gossip and discussion that resolutely protects them. Challenging this isn’t easy, and changing it is even more difficult. Prospective leaders can’t challenge it, because the key holders decided on whether they get promoted or not. Those brave enough to challenge it are often committing career suicide…

It’s a pretty good, self sustaining eco-system, and changing it is like screwing with the organisation’s system of natural selection. If you want to lead, dabble at your peril…

The key thing for existing leaders to realise is that change is necessary, and this is not always an easy realisation. It is the job of strategic leaders within the organisation to orchestrate this realisation and there are a myriad of ways to make it happen. Once this is reached, the hard work begins. Many across the country have tried for many years to get real change in culture, especially around wellbeing and emotional intelligence, but it hasn’t stuck or sufficiently shifted yet – the guard has not changed. The self-sustaining eco-system has prevailed.

If you are reading this as a leader, recognising the facets of promotion (purely experience based) above are less than adequate for selecting potential leaders is a step in the right direction. If you are an aspiring leader, influencing how they are organised and run is a priority. If you are a serving cop, acknowledging that experience isn’t everything yourself is a big start, and even having open discussions about it all helps.

Re-wiring how we see leadership isn’t just something that can be dabbled with, it’s fundamental to the police’s existence in the future. If we continue to use experience as the defining feature of leadership selection, then no true change will take place. And we need to change, if only to address the wellbeing of the people that work for the police as an organisation. A learned friend (not in the political sense obviously!) and serving Inspector once said to me in a well received Twitter DM:

“The trouble with the cops, is that there aren’t enough nice people who are cops.”

It resonated quite strongly with me, as being nice to people (and by nice I don’t mean pink and fluffy, I mean caring about people) often didn’t seem to rear its head as a standard feature of leadership in my constabulary at that time. Maybe it’s time the police looked at who holds the keys to the gatehouse, and whether they themselves believe that a move away from experience as the primary definer of competence is something more than just ‘garlic bread..?’

Talk is cheap, it’s active change away from experience that needs to be seen by those in service now, and more emphasis on leadership qualities that are distinctly counter-culture needs to be established. This isn’t just a changing of the guard, it’s a removal of them as holders of the keys, followed by establishing a new guard that doesn’t listen to the people in the keep. It’s not cosmetic surgery, it’s genetic engineering, looking and re-addressing the way that we both evaluate and develop leadership at its basest level.

It’s about replacing:

“How many years service do you have?” or…

“Have you done your time on Neighbourhoods?”

With:

“What kind of leader are you, and how do you know?”

“What have you done to develop yourself (not your skills) for this role?”

“What would others say about you as a leader?”

Recognising that leadership is a skill in and of itself, and is not solely reliant on experience is a start, but physically developing and harnessing that is the challenge. Because:

And we’ve been doing it for a very long time.

Personally I have aleays thought that good leadership is an attitude, a personal quality. I met (and worked with) some exceedingly good leaders and also some awful ones. However it was seldom about what they had done, where they had been or for how long. It was almost always about who they were. I don’t even know if it can be taught, but the brst leaders almost always rose to the surface but weren’t always popular with the SMT. Occasionally you would hear a group of PCs discussing a particular Inspector “I would follow him/her to the end of the Earth”. They almost always led by example, led from the front and were FAIR. I’m sure we all know a handful, but not many

LikeLike

Agree totally with this blog. In so many ways leadership is about promoting effective environments. Environments where people understand what their role is about and where they are encouraged and supported to be creative in their problem solving ( if it’s ethical and likely to work, then do it)…environments where they are encouraged to think about situations, analyse them and seek creative solutions. Environments where they are encouraged to question, to challenge and to think around situations. Obviously in the context of understanding where and when it’s appropriate to question…..

LikeLike

Sadly the police service cannot distinguish between leadership and management. In my opinion and reflecting after a long career in policing they are two DIFFERENT skill sets. It was rare to meet a leader, one that you would follow – even at high personal risk. Such leaders rarely appeared in the management sphere at headquarters, where decision-making was very different.

This simply got worse in the last fifteen years. The police service that extolled diversity (largely in response to external demands) become far more intolerant of dissent, even from those who advised the decision-makers. Those that reached the “top” were all too often slick at presentation, making decisions over time and “working with partners”. They were not leaders who could inspire and ensure those they commanded followed them.

Why else did we get ‘tactical advisers’ and the ‘bronze, silver and gold’ command structure?

Those who could ‘lead’ rarely sought promotion to senior ‘management’ posts.

LikeLike

A few comments from me.

First, this isn’t new – it could have been written when I joined (by the way, I’ve probably done more years in the job than you’ve had hot dinners, laddie). Time served is a shorthand guide to skill, attitude, etc. Not always reliable or that accurate, but provides a starting point.

Second is the important point about gate-keeping. The focus is usually on the promotion process, not on the hurdles that have to be crossed to get to that stage. If you can only get a recommendation for promotion after serving time on a neighbourhood team, how do you secure a poisition on a neighbourhood team?

Third, maybe we should see leadership as a specialism in itself? A team leader (inspector?) and certainly a senior leader will need to know about operations, finance, HR, investigations, and maybe some specialisms. Importantly (as you argue) they need to be good leaders. And ideally a blend of all those skills.

What’s missing are options of promotion within a specialist function, for roles where maybe the specialist skill/experience is more important in the ‘blend’ than leadership. This is something that has changed since I joined. In those days there were separate promotion streams for CID and uniform, and leadership specialist functions appeared to be much more ‘planned’. A single promotion process was intended to improve diversity and fairness – but many would say that hasn’t worked. It can also leave forces exposed when trying to fill roles overseeing specialist teams.

Alongside this is the continued linking of ‘progress’ with promotion. For the Winsor Review, ACPO proposed more flexibility to recognise and reward staff with specialist skills or in exceptional roles, but this wasn’t supported. It means promotion is seen as the only means to ‘progress’. It means that skilled officers often have to move into units where they are probably less effective. It disrupts the development of advanced specialisms. Yet if you look at the way current single system works, and in particular the pre-promotion hurdles, maybe the previous way was ‘fairer’?

LikeLike